International law in African universities is still taught within a rigid Eurocentric context. Changing this is important, but also incredibly difficult given how entrenched the current approach is.

Surprisingly Nigerian musician Fela Ransome-Kuti (1938 – 1997) might have something to offer in helping crack the problem. The Afrobeat pioneer has a lot to offer any teacher wanting to decolonise the teaching and understanding of international law.

The curriculum of international law in many African universities, like those in Latin America and Asia, still links seminal moments in the development of international law to European history, and refer to European thinkers as “fathers” of the subject.

There is little or no reference to how non-European civilisations have contributed to the development of international law or the role international law played in entrenching colonialism.

As such, the curriculum excludes the discussion of diplomatic interactions between and among pre-colonial African Empires, and with European and Asians, especially as it relates to trade, conflict resolution and recognition of statehood. In addition, there is little consideration of critical works that have exposed the bias underlining the practise of international law.

These exclusions have raised the importance of decolonising the teaching and understanding of international law. This process requires the consideration of wide-ranging, innovative and multifaceted approaches. One is the inclusion of voices and narratives beyond academia, especially artistes at the forefront of exposing global imbalances and Eurocentric dominance.

Fela is an important source because he was a revolutionary as well as an intellectual who was steeped in the struggle against social injustice in Africa. His music speaks to issues that are raised by critical scholars on the need to reform the teaching and practise of international law . These include issues such as illicit financial flows from the global South, the marginalisation of Africa on the world stage and the masking of Eurocentric values and opinions as “universal” standards. Fela was able to use his radicalism and eloquence to expose this unjust order of things.

Fela’s background

Fela came from a university-educated, politically active family. His mom, Funmilayo, was a teacher, women’s rights’ activist and feminist. She was associated with some of the most important anti-colonial educational movements in West Africa. She was the first Nigerian woman to drive a motor car and a member of the team which negotiated Nigerian independence from Britain.

Fela’s father Oludotun was a pioneering headmaster, the founding president of Africa’s largest professional group, the Nigeria Union of Teachers, and an Anglican priest.

Both Fela’s brothers were medical doctors and human rights campaigners.

Fela was strongly influenced by his family – including his cousin, the writer and political activist, Wole Soyinka.

Of course Fela was his own person. He was also supposed to study medicine, but switched to music.

The way in which he used his music as a weapon makes him particularly useful in the classroom.

Bringing Fela to the classroom

Fela used his music to tackle the marginalisation of the downtrodden and global injustice. He also preached the need to put pan-Africanism at the centre of sociopolitical and economic processes. His non-conformist, radical stance on these issues ensured numerous arrests, harassment and torture in the hands of successive military regimes in Nigeria.

Fela’s infectious beats and critically engaging lyrics, mainly sang in Pidgin English, and his intense and methodical delivery, provide an important window to exposing students to critical understanding of the global system.

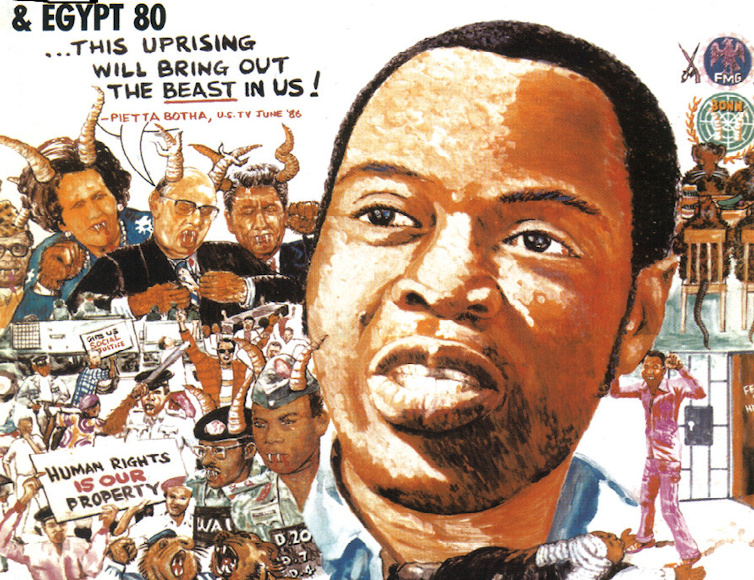

Two of his songs are relevant to the critical teaching of international law. These are “International Thief Thief” and “Beast of No Nation”. Both reflect issues raised by critical movements, such as the Third World Approaches to International Law, a network of scholars who explore the inherent contradictions and inequality of the global system.

In “International Thief Thief” he addressed illicit financial flow from Africa:

Many foreign companies dey Africa carry all our money go (Many foreign companies operating in Africa illegally take our money out)

Dem go write big English for newspaper, dabaru we Africans (Then they will write complicated English in newspapers to confuse us Africans)

Dem go cause confusion, cause corruption, cause oppression, cause inflation (As a result of this] they cause confusion, corruption, oppression, inflation).

In “Beast of No Nation”, he sang about the unequal structure of the United Nations:

One veto vote is equal to 92… or more

What kind sense be dat? (Where’s the sense in that?)

Na animal sense (It is animal sense).

In teaching global institutions under international law, Fela’s “Beast of Nations” could be used to show students the problematic structure of the United Nations where only five countries wield veto powers (http://www.un.org/en/sc/meetings/voting.shtml).

It could also show how dominant interests determine intervention measures by the UN, and the exclusion of nationals of countries in the global South from becoming the heads of IMF and World Bank.

“International Thief Thief” is a good material for exposing the role of multinational corporations in illicit financial flows from Africa and their complicity in environmental pollution and corrupt practises.

Disrupt underpinnings

African law schools have to be more open to interventions that can help disrupt the Eurocentric underpinnings of the teaching of international law. Music, poetry, literature and films can help do this. Their inclusion in the curriculum hold immense benefits for students and lecturers alike.

It would also help reinforce the understanding that law does not – and cannot – exist in isolation. It should flow from the social reality and context of a society, and in turn seek to genuinely address real problems.

![]() Fela has left us with critical material. The question is whether we are bold enough to channel them into changing the status quo. This is part of my ongoing research in this field.

Fela has left us with critical material. The question is whether we are bold enough to channel them into changing the status quo. This is part of my ongoing research in this field.

About the Writer

Babatunde Fagbayibo, Associate Professor of International Law, University of South Africa wrote this article which was originally published on The Conversation.