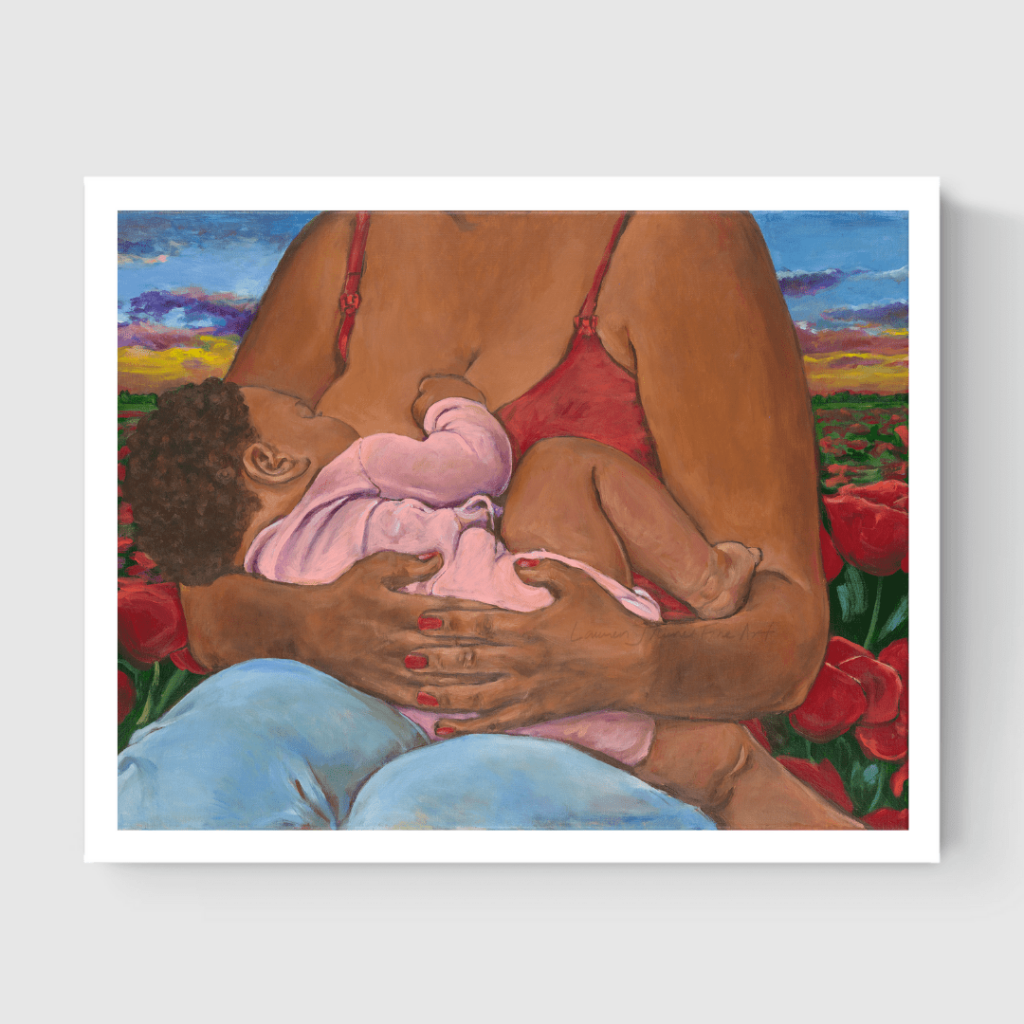

image Lauren J. Turner

Nwaka wishes there was another way than this. She ransacks herself for any humanly reasonable explanation, shakes out the recess of her heart (does she even have one?) – nothing. Split her into two unequal halves; the larger part, reluctant, wants to remain on this plane, with this human child she’s known to love. The other half, selfish, loyal to a separate world known and comprehensible to her alone, wants out of this life, to glide between universes without the weight of embodiment pressing down hard on her bones. When she drops her boy, Divine with Jeremiah’s mother, Nwaka stoops so they are the same height;

– Be a good boy, eh, she tells him. Mummy will come to get you soon, you hear? A lie.

Divine nods twice. She tugs at his chins, pulls him into her bosom, against the gbim-gbim in her chest — uneasiness manifesting through clammy palms and stinging eyes.

Nwaka knew the routine. She had mastered it too well, why was letting go hard now? It was easier when she left the woman from Okene who thought she could own her completely. The insolence. It was to be expected with humans; selfish, mindlessly selfish. She had pitied the woman after she came several nights to the bank of the Nwali river, stripped to her primitive form, wailed and wailed for a child, her humility so palpable she could not ignore as it developed sturdy hands and reached around her throat. On one such night, she climbed out of the water, and followed the woman home, out of pity solely.

At first, it was good; the woman, never leaving her sight for longer than a second, always buying her things, even when she earned little from her provisions kiosk. Until the woman started moving mad after she’d turned six. It began with the woman’s husband dying, and then strange men started visiting their one-room apartment; the woman locking her out of the room to sleep on the cold corridor when these men came around(what nonsense!), and the woman hitting her one morning with a twisted wire because she wet their floor-mattress. Her transformation was never something Nwaka, then named Anwulikalili, would have anticipated. But when it began, it continued growing, till that small woman she had shown grace at Nwali river was no longer there. The woman apologized after the first time but did not stop. Night and day, the woman abused her for flimsy reasons. Like the night that she pressed the kerosene lantern into her back because Anwulikalili was wasting costly kerosene writing her school assignment. Why didn’t she do it when there was daylight? Or the afternoon she gathered all her ragdolls in a heap with the rubbish, poured kerosene on it, and lit a matchstick to it. Anwulikalili watched as the plastics melted hands to torso to legs, till what remained was the charred head of one of the dolls.

The night before her eighth year with the woman, Anwulikalili manipulated her body till it burned fierce hot coal from the inside out. She wanted to pepper the woman. She watched in mischievous delight as the woman scampered around the room in search of medication, begging her to not leave, to not die. She immersed Anwulikalili into a basin of cold water, but still, she pulled fire from the deepest of hells into her body till everything inside was roasted and she quietly slipped out through Anwulikalili’s mouth, past the woman who had assumed the same form as she did that night she came to beg. She had quietly slipped into the night and back into the river.

*

When Nwaka sniffs the Johnsons shampoo in Divine’s hair, she glimpses then what her mistake had been: she should’ve left long ago. She’d grown too soft, too human. She’d disregarded the simple format mapped from genesis: they were interlopers, not permanent residents. Nwaka had handpicked this identity that she did not own, had tried to possess it; the same way she’d possessed the boy. Now was time to fix up. But why today?

If not today, when?

Nwaka hurriedly finishes the hug, slaps Divine’s backpack as he walks toward his grandmother. She straightens herself despite the mass of sadness pressing hard upon her, manages a weak smile for this woman who could not bring herself to accept a daughter-in-law with no known background.

( – Where is she from? she’d inquired of Jeremiah at their introduction.

– Who are her people?)

In the car, Nwaka succumbs to the grief in her chest, bangs her head against the steering till there’s a small gash and blood begins to drip.

Before Jeremiah, no human had ever walked out on her. She was always one to make the exit, sever the cord. But Jeremiah was a bastard shaa. This might be a different story had he not carried his big head to go die, a reckless car accident, the day Nwaka went into labor. Or if she had left before he sweet-mouthed his way into her head. But she’d let it happen. And as the baby destroyed her intestines, struggling to taste this world’s air, Jeremiah was in another theater, his head split in two, fighting to keep his life.

Divine became the only string that tethered Nwaka here. She’d named him, months after his birth, for the way his eyes glinted like small orbs. She’d fed him, watched him babble, crawl, walk, grow – all that humanly stuff. And she’d been fascinated by it all.

Now? She couldn’t ignore the pricking to be removed from this body.

Nwaka starts down the road, her head spinning, shoulders heaving. Memories from this life kaleidoscoping before her eyes; that aloof night on New Year’s eve at Ballroom where Jeremiah, drunk-eyed, had asked to dance with her and she’d obliged. When he’d asked with bated breath, again? Nwaka had agreed almost immediately, because although she’d just met this stranger, something about the surety in the way he gripped her waist and rolled it to the rhythm of Nwa Baby blaring from the surrounding speakers, made her melt away. She recalls Divine gripping her similarly in a parting embrace, the memory rolls into full-view and pauses.

At that moment, Nwaka realizes that more than shuttling freely between parallel worlds, she desires the completeness that love promises and the safety in a warm embrace.

About the Writer

Daniel Ogba is an Igbo-Nigerian writer and undergraduate student at the university of Nigeria, Enugu campus. His works has appeared in Ile Alo, the Muse journal 47, Everyday Journal Issue 2 and elsewhere.