On the Road from Benin, I must have been asleep for a thousand and one years. The clamour for food that seemed to be the concert every nerve in my body was singing in, was horrifying. My entire body was like a museum of pain coming from parts of me that I didn’t even know existed. Each disparate pain tried to maximize itself in a bit to swallow the others; each calling me to take a look, to see what damage had been done. It is always the case that pain demands attention, it doesn’t matter whether one can assuage it or not, pain is like a new born baby which will not stop crying even if a thousand teats were fastened to its lips.

Drowning in the sea of pains, the unmistakable coarseness of where I laid stood out like the sun, asking me to make sense of it. I had only recently bought a double fibre filled mattress, you see, after much persuasion from Ramatu, who had gone from begging to swearing to finally threatening not to share my bed anymore. I can chest the begging and the swearing; taking me back to my incel days, however, is where I draw the line. Ramatu is my longsuffering girlfriend. When everybody else chose to become judge over my life, she chose the role of an uninterested court attender who is perfectly content with the spectacle. I knew that she judged me, it was evident from her eyes that she did but not in a thousand years would you see my Ramatu joining all the others in their stone casting. Whenever I think of her, I think of the silence that speaks, it says I may not be happy but I will be here.

My first fear when I realized that my new mattress may have been stolen in my sleep was that my Ramatu would leave me. I tried to swing my body up to investigate the room but the concert of pain pulled me back. There was no swinging my body up, I had to ease my body up. Slowly. I sat up and was astounded for the first time, to see that the coarseness wasn’t because my soft, new, love mattress was stolen. This is not my house!

I tried to remember where I went the day before so that I could make sense of where I was and why I was there. This place did not look like the place of anybody I knew. Heck, it didn’t look like the house of anyone I could know. It was well beneath my wage bracket and I am the first to admit that I am a snob. I’ve always been. People love to blame my snobbery on my mother who, after she was taken from the village to Abuja by my father, basked in her good fortune and immediately transferred the hatred she had always had for herself, to the people she had left in the teeth of poverty.

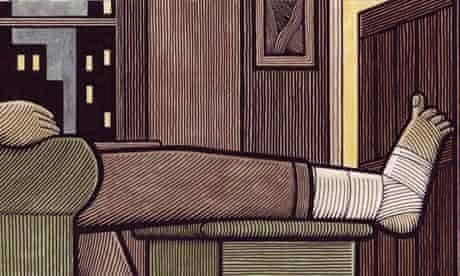

After easing the weight of my body on my buttocks, I was able to finally see myself. To feel myself even. The pain that won my attention at this point was the one coming from my leg. A dirty strand of wrapper adorned a portion of it, obviously serving as a tourniquet. I knew there was a story I was missing here, I just couldn’t seem to grab it from whatever tissue of my brain was responsible. I had only my spandex shorts on me and I wondered how and when I got undressed.

My eyes impulsively carried me round the room, in search of a door and I wondered if the wound that was eclipsed by the dirty tourniquet would let me walk. I wondered if at this moment of fear, flight was an option. Fight, obviously, wasn’t.

‘Thank God you are up. I was almost certain you’d die and I would come to regret listening to the insistent voice.’

Whatever asymmetry meant, this man embodied it. He had a small head on a large neck resting on narrow shoulders. I couldn’t make out whether he was fat or thin because he had a jumbo-sized belly that seemed to be busting at the seams and this belly was attached to a slender torso. His voice was like that of a child and he looked nothing like the impeccable grammar he spoke.

‘What insistent voice?’ I had so many questions but this was the only one that escaped. The presence of this mystery man immediately overshadowed the concert of pain and mystery. I was suddenly looking forward to answers and he would provide them. He had to.

‘It is the voice that never allows me to pass by. It is always tugging at my heart, compelling me to give out a penny, help an old woman with her luggage, or do what I did with you.’

‘What did you do with me?’ I asked, both alarmed and afraid.

‘You were lying in a culvert when I saw you in a puddle of your own shit and blood. I wondered why you were there at around 2:00am. At first, I thought you were mad, then I thought you were dead. All the while, I kept walking my path but the voice wouldn’t let me be. The last time I refused to listen to it, I went through the purgatory of self accusation which later transformed into self loathing. Its verdict was that I was the worst specimen on God’s earth. I did not want to relive that experience.

‘So, I am not kidnapped? Thank God! I was almost afraid.’

‘Well, if you have kidnap value, you’d better warn me ooo, as you can see, I may need some extra cash.’ He laughed. It was funny to him but I knew I would never find what he’d just said funny because there were still more questions than answers and I may yet have been taken by a kidnapper who arguably had the worst sense of humour if there ever lived one.

‘Now it is my turn to ask questions’, he said, ‘how did you get there? What happened?’

Again, I tried to conjure all that I knew about my life. Every moment that led me here but nothing came to me. Every vivid memory I had came to me but I could not say how I got to the middle of the street by 2:00am soiled by my blood and faeces.

‘I do not know’, I tell him, ‘I only know that my name is Musak and I used to be an alcoholic. I am a public servant…’

‘Wait! This used to be an alcoholic part, how long ago is used to be?’

‘I haven’t had a drink since my mother died, two weeks ago. It was her dying wish that I dropped the bottle.’

‘In my experience, our oaths to dying wishes gets cold with the dead bodies of those whose wishes we try to keep. And we shouldn’t feel bad about it either. Why should you hold your life up to the standard of someone who could not live as long as you have? If you outlive them, it’s probably because you are doing something they aren’t. think about it.’

Hearing him say these words, I instantly felt the urge to die if only I’d be spared the agony of hearing him speak some more. Fortunately for the both of us, a smile creased a side of his lips and I saw that he was just messing with me. The smile seemed to suggest, however, that he was truly asking to know if I did not go back on my promise the night he found me. I hated the superphilosophy he was trying to throw at me about my oath to my dead mother when I do not even know his name.

‘My name is Kaiza,’ he says, ‘I work all kinds of jobs. I am not a hustler though, I’d prefer to be called a survivor. The hustler name has all sorts of dirt around it lately and I keep my hands clean.’

‘Why are you a survivor though? Can’t you look for a decent desk job and live…’ I look round the space as I say this ‘… a more decent life?’

Kaiza’s rambunctious laughter was almost infectious. Were it not for the fact that he seemed to laugh at some assumed folly of mine, I would have joined in his laughter if not for anything, to spite the concert of pain that is suddenly demanding of my attention.

‘You are a well fish, unaware that there are other water bodies housing other fish living other lives. You think everybody can just decide to take a desk job and poof! It happens? Today is the first time I am truly believing that this country houses two countries.’

‘You misunderstand me. All I am trying to say is that there may be something better for you to do than just hustle… er… survive’. I said trying to minimize the stupidity that my sheltered life had dealt me. For the first time in my life, I wished I were a poor so I would know what life is like in other rivers and other lives.

‘Let me see what’s happening beneath the rag.’ He said, neglecting what I had said. It was almost as if I had not said the anything and I desperately wished it were so. I should have chested my L in peace.

When he untied the tourniquet, it was the biggest wound I’d ever seen on a human being. I cringed so hard, you’d think I was staring at it from a safe distance. There must be something about the brain that makes it worsen a pain because it is suddenly seen because as soon as I saw the wound, the concert transformed into a senseless din both dizzying and horrifying me.

‘Let me get you some Aspirin.’ Kaiza said and left.

Left alone and satisfied that I had no reason to fear for my life, I realized why I had chosen the bottle all those years ago. I suck at keeping myself company. Before long, I was thinking about how no one ever cared for me and how even if I had died no one would ever know because no one would go in search of me. I remember my mother and the story she had told me on her dying bed about my great grand aunt.

My great grand aunt lived a very long and plagued life. She was ill one time and my mother decided to bring her into her care to nurse her because she felt that Iyya had reached extremis and would want her to get some care before she died. Iyya was the happiest she had ever been when she came into my mother’s care. She said so herself. One day my mother decided to shave her pubic hair before bathing her and after she was done, Iyya exclaimed that it was the freest she had felt in a hundred years (she always spoke as if a hundred years ago happened just yesterday).

‘I remember when my husband went for his philandering and brought home a gift’, she told my mother. ‘It was the gift of lice he got on the pubic hair of his prostitutes. I was so happy that he got those lice because they made him so uncomfortable. I was uncomfortable too because he gave them to me but his discomfort made light the burden of mine’.

The day they shared this story, they almost laughed the ceilings down. The next day, Iyya died. She was happy and her pubic region was ventilated.

In the middle of my thoughts of Iyya, I remember my Ramatu. I wanted, at that moment to know where she was and what she was doing. I wished I could somehow conjure a mirror that would show me her current estate but more than that, I wished she was miserable wherever she was. It would kill me to find out that her life did not stop because she couldn’t find me. Maybe it is my fear that fills up the void I had always carried in my heart because for the first time in my life, I was in love with Ramatu and there was nothing I wouldn’t do to see her again, to feel her again, to take her to my soft, soft bed and show her how much her presence in my life means to me.

Kaiza walked in holding a dirty cup which he gave to me. It housed some unclean water which I almost refused to drink but later made up my mind to because I hoped the placebo effect would kick in. he handed me the tablet and I gulped it down hurriedly so I would not catch whatever smell may accompany the water. I almost threw up.

‘Do you know any phone number we can call? I need to get you off my hands because a survivor can’t carry no burdens.’

‘I don’t’ I said, ‘but you can take me to my house, it will not be hard to find.’

‘Where is your house?’

‘It is in an estate in Asokoro’.

At the mention of Asokoro, his jaw dropped.

‘Is there an Asokoro in Benin?’

His question dumbfounded me. Interestingly, it had the same effect on him. I wondered what had happened the night he found me and for some reason, I felt lucky that they did not find my corpse instead. ‘How did I get to Benin?’ I wondered.

Conflicting thoughts filled my mind and I wondered if it wouldn’t have been better if I’d died in that state of oblivion. It would have been glorious to die without being present at my own death. I would have been spared the indignity of the pain and I certainly wouldn’t have pleaded. I would simply ease into nothingness or whatever will confront us behind these veils.

Whatever my story is, I am sure it cannot be about ritualists who take me to the evil forest and are unable to use me because I had a strong spirit. My spirit is the weakest spirit if one ever existed. I am merely a floating soul inhabiting a privileged body which resides in a well.

When I leave Kaiza’s house, I will leave with a glue to my lips; mum about the events that I myself cannot remember. No one will hear that I have been to Benin. Well technically, I have never been to Benin. I only returned from it with a huge wound on my leg, a forgotten part of my own story and the painful reminder that the shelter I have always enjoyed as a result of my father’s wealth was a weakness.

The same way I will never know what happened the night Kaiza found me, is the same way no one from my life would ever hear that something even happened. I will not give anyone yet another chance to judge me. This story is one for me and my grave.

About the Writer

Kodun Musa is a postgraduate student in the university of Jos where he currently studies Literature in English. Most times, he loves to play football and to read. When the stars align, he can be found writing as well. He lives in Gombe with his wife and kids.