As the ruling APC assail the nation with pictures of President Buhari’s visits to troubled states The Guardian put forward some solutions as it straddled the recent massacres with a history of violence in Southern Kaduna in this editorial of March 9th, 2018. Read on….

———————————————————————————————————————————-

Those who are familiar with the history of conflict in Kaduna state would not wrestle against the point that, in the more than three decades of violent clashes between people along the religious or whatever divide, nothing has been achieved in the way of a concrete victory for either side.

The reality of the situation in Kaduna, therefore, is that of a pointless fatal struggle among neighbours who only have not taken conscious, positive steps towards understanding and/or accommodating one another.

From the 1981 land-driven killings of Kasuwan Magani to the recurrent religious-cum-political violence in Kafanchan, the destruction of lives and property in the southern part of the state has had a tragic Shakespearean ring to it: full of sound (and fire) and fury, signifying nothing.

Recently, in the same community of Kasuwan Magani where the landmark massacre occurred over thirty-five years ago, mortal acrimony reared its ugly head again. And its excuse for being is an old, familiar one: religion.

For, according to reports, the “attempts by Christian and Moslem youths to stop their girls from dating their male counterparts from religions different from theirs was the major cause of the violence.”

In this latest regress into unreason, residents have been killed, houses have been burnt, and the fragile hope for an enduring peace that had been so assiduously kept is yet again broken. It will take another long and tedious round of work to repair the peace and bring the community back to a semblance of itself.

In this age of enlightenment in which the benefits of global exchange and inter-faith discourse are well known (or at least easily retrievable), and in a supposedly secular state as Nigeria is, how do people still get around to murdering each other based on religious sentiments? Why is the level of tolerance for otherness so low, and that of suspicion so high, that inter-marriage (or mixed relationship) is still a forbidden thing, punishable by death? It is remarkable that both Islam and Christianity have been characterised as religions of peace.

Why then do some of their adherents appear ever-ready to slip into the bestiality of violence in order to maintain the purity of their own supposedly peaceful faith?

The disagreeableness of the recent situation in southern Kaduna, and therefore the urgency of the foregoing questions, are well captured in the ensuing comments of the Public Relations Officer of the Christian Association of Nigeria, Reverend John Hayap.

Nauseated, as any right-thinking human should be, by the news of the incident, Hayap pointed out the sadness of the fact that “in this age of education and technology [people are still] fighting and killing each other because of religion or boyfriend and girlfriend matter.”

Even “if they don’t have good knowledge of their faith,” said Hayap, “their exposure to this modern era should help them stop this shameful act.” Characterising the acts of violence also as “a display of a high level of ignorance,” the cleric appropriately urged his Christian colleagues and Moslem counterparts to “step up their teachings” in order to stem the tide of fundamentalism.

It is clear that the lack of proper education has come up as a major contributing factor to the eruption of religious violence in Nigeria as a whole. This is very true of Kaduna, and in this regard the administrative head of that political space has an important role to play.

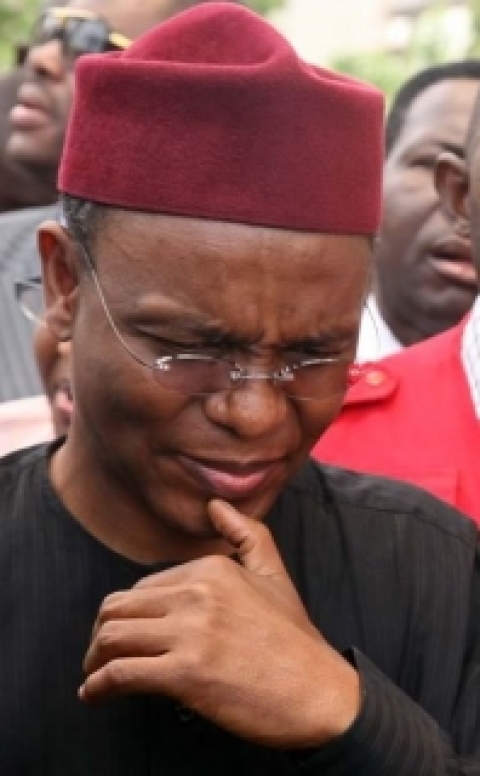

It is good that Governor Nasir El-Rufai has ordered the arrest and prosecution of the suspects in this latest manifestation of the ugliness of fanaticism. El-Rufai’s humanity and sense of duty, in quickly sending out relief materials to the affected people, must also be commended.

However, the governor must go beyond these merely reactive measures and begin to forestall occurrences of religious (or any other form of) intolerance.

The state should educate its people on the importance and value of tolerance, and rally them towards the path of peace. Setting up a government initiative on religious tolerance, or indeed including Peace Studies as a compulsory subject in the primary and secondary school curricula, would not be out of place.

There is no true development without peace, and no person or party can lay claim to political savviness amid the corpses of its people and the ruins of their property.

Mallam El-Rufai and his ruling APC party should, therefore, treat this as a matter of great urgency.

Finally, studies suggest that no matter how thick and dark the barrier of understanding has become between two warring factions, no matter how long the history of hostility between them, it is never impossible to trace that history and fashion a passage through the barrier so that there can be better relations between both ends of it.

The people of Kaduna state need to understand that, rather than being on a one-way street of bitter rivalry along whatever lines, they do have the option of peace and mutual understanding only if they are willing to take it. They also need to understand a fundamental truth about religious worship, expressed in the paradoxical but wise saying of a sage: “He who kills for the love of God kills love, kills God.

He who kills in the name of God leaves God without a name.” This lesson is, indeed, for all of humanity.