Video footage of a man in Paris scaling four floors of a building to save a child dangling from a balcony has gone viral. The man, Mamoudou Gassama, a 22-year-old undocumented migrant from Mali, arrived in France only a few months ago following a perilous journey through countries including Burkino Faso and Libya and across the Mediterranean. His seemingly superhuman rescue earned him the nickname “the spiderman of the 18th” after the district in Paris where this act of heroism took place.

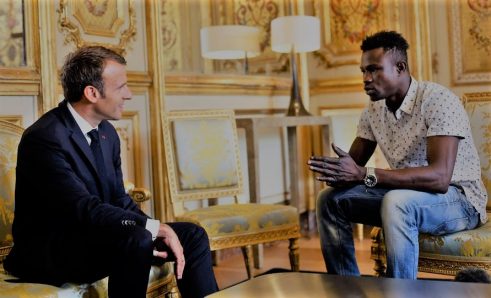

That Gassama deserves full recognition for this outstanding act of bravery is surely beyond question. His actions have been lauded around the world. But perhaps the greatest honour came from a meeting with French president Emmanuel Macron, who presented Gassama with a medal in recognition of his “bravery and devotion”, a job with the Parisian fire brigade, and also with a promise: French citizenship.

Gassama received residency documents enabling him to remain in France legally, and was told he would be fast tracked to full citizenship.

For an undocumented migrant who risked his life crossing land and sea to reach France, only to find himself living in the shadows as a consequence of being “sans papiers”, or undocumented, citizenship is a highly prized status. It is the prism through which obligations between a state and a person are understood. Without citizenship, a state will likely refuse to recognise any obligation towards a person unless they can prove a special reason for why they should be treated as the exception – for example, because they are fleeing conflict or persecution.

A move towards ‘earned’ citizenship

As such, it’s little surprise that Macron viewed citizenship as the ultimate reward for Gassama’s bravery. But the hypocrisy of this in a country with highly restrictive immigration laws hasn’t gone unnoticed. There are also precedents set for this within French law. Article 21-19 of the French civil code states that a person can be granted citizenship as a consequence of performing “exceptional services” for the nation, and has traditionally been applied in the case of Foreign Legion soldiers from other countries who fight for France.

Yet the case is also part of a wider international trend in which citizenship is conceptualised as a reward to be earned through good behaviour. In the context of heavily restrictive immigration laws in Western countries, rewarding migrants with citizenship has become a means through which the state defines the deserving future citizen from the undeserving non-citizen.

This trend can be seen in French citizenship law, whereby prospective citizens, barring some exclusions, are subject to a contract which requires them to prove, over a two-year period, that they deserve to stay. While this reflects the historical importance of the idea of citizenship as a contract between citizens and the state in France, it’s also novel in emphasising the duties of the citizen not only in citizenship itself but also in the process of becoming a citizen.

This trend can also be seen in the UK, where prospective citizens must pass the “Life in the UK” test. They must prove a certain level of English language skills and demonstrate qualities of good citizenship such as obeying the law and paying taxes through employment before they are granted naturalisation. And it also underpinned Barack Obama’s DREAMers scheme, under which undocumented children would be rewarded with citizenship if they attended university or served in the army for at least two years. These are but a handful of examples of a trend which is shaping access to the basic rights of citizenship in countries of high immigration around the world.

Rights at stake

But this trend is concerning. Citizenship once represented a set of rights to be demanded from the state as a form of emancipation, for example in the civil rights and suffrage movements. But increasingly this notion of citizenship is being replaced by citizenship as a reward for loyalty and obedience. It has, in countries such as the UK and the US, become a conditional reward that can be removed, with citizens at risk of being stripped of their rights and rendered stateless should they disobey the state. This means that citizenship status is increasingly hard to access and precarious, and a person’s basic civil, social and political rights are undermined as a result.

![]() Gassama’s actions were near superhuman and they rightly earned him international recognition. He was also, rightly, granted basic citizenship rights in the country in which he resides. But citizenship rights shouldn’t be about being superhuman. Rather, we have to find another way of allocating basic rights to people simply by virtue of their humanity alone.

Gassama’s actions were near superhuman and they rightly earned him international recognition. He was also, rightly, granted basic citizenship rights in the country in which he resides. But citizenship rights shouldn’t be about being superhuman. Rather, we have to find another way of allocating basic rights to people simply by virtue of their humanity alone.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Katherine Tonkiss, Senior Lecturer in Sociology and Policy, Aston University